Contact Us

Phone:

Email:

Location:

1234 Street Name, City, State 12345

Hours:

Mon - Fri 8am to 4pm

Minorities Reap the Benefit When Affirmative Action Ends

Colleges across America see the first signs of a repeat of what happened in California after 1996.

By Jason L. Riley

The Wall Street Journal

September 10, 2024

What should be a college’s priority in choosing a student body? Should it be racial balance? Or should the primary focus be finding people who are likely to thrive at the institution regardless of their ethnic heritage?

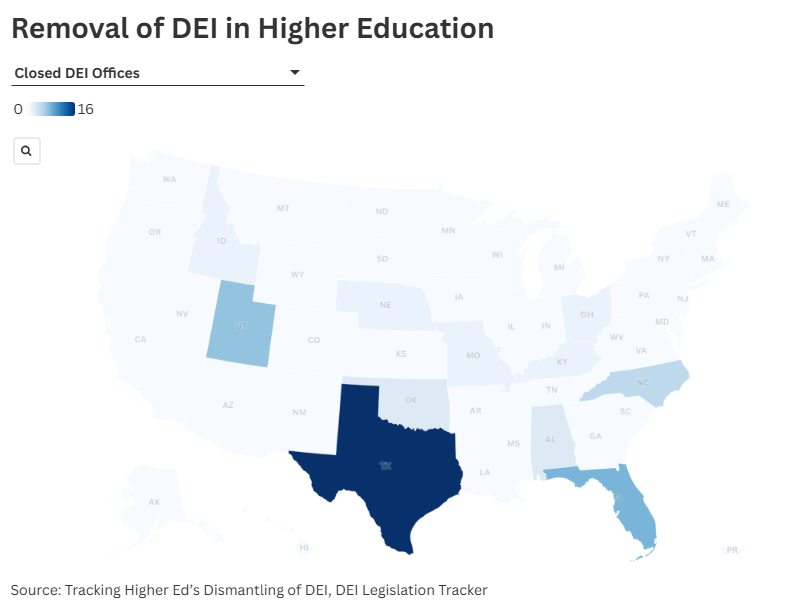

Defenders of affirmative action insist that there is no trade-off between those objectives, but new demographic data on incoming freshmen at some of the nation’s most selective colleges tell a different story. This year’s entering class is the first to be admitted since the Supreme Court ruled last year in Students for Fair Admissions v. Harvard that race-conscious admissions policies violate the Constitution. Reports so far show a decline in the share of black students entering such top-tier schools as Amherst College, Brown University and MIT.

Media outlets are griping about the subsequent decrease in “diversity,” but at some schools the enrollment of Asian applicants rose, as did the number of first-generation college students. At Yale and the University of Virginia, black enrollment barely changed, while it ticked up at Bates College. Robert VerBruggen of the Manhattan Institute has noted that without detailed admissions data, which colleges historically have been reluctant to release, it’s hard to determine whether schools are fully complying with the decision.

Nevertheless, because admissions offices can no longer use double standards to select black applicants, a decline in black enrollment at the nation’s highest-ranked colleges was to be expected. That’s what happened in California and other states that prohibited colleges from choosing applicants based on race before last year’s Fair Admissions ruling. In the Golden State, where Proposition 209 banned affirmative action in 1996, the initial reduction in black and Hispanic students was more pronounced on the most selective campuses, UC Berkeley and UCLA. But as the New York Times later reported, “eventually the numbers rebounded” and “a similar pattern of decline and recovery followed at other state universities that eliminated race as a factor in admissions.”

More important, however, black graduation rates rose sharply after racial preferences ended and more students were funneled into schools throughout the University of California system that better matched their academic qualifications. The obsession with the racial composition of first-year students at elite schools is misplaced. The more consequential metric is what percentage of black students in the Class of 2028 make it to senior year and graduate with a degree in their intended major.

Before California’s prohibition on racial preferences, black enrollment at UC Berkeley had been growing, yet only about a quarter of black students were graduating within five years, compared with two-thirds of white students. The end of racial preferences prompted a redistribution of students. System-wide, the number of black and Hispanic freshmen who graduated in four years increased by more than 50%, as did the number who earned STEM degrees and graduated with grade-point averages of 3.5 or higher.

Blacks and Hispanics admitted to the UC system’s most selective schools likewise benefited. “Prop 209 changed the minority experience at UCLA from one of frequent failure to much more consistent success,” wrote Richard Sander and Stuart Taylor Jr., in their empirical analysis of affirmative action policies. “The school granted as many bachelor’s degrees to minority students as it did before Prop 209 while admitting many fewer minority students and thus dramatically reducing failure and drop-out rates.”

If the share of black freshmen at our most competitive schools goes down while black graduation rates ultimately rise at those same institutions and elsewhere, how are black students in general worse off? Having minorities on campus allows prestige schools to showcase and market their racial diversity, but black students who are admitted with lower standards than other groups get a raw deal. What is the point of struggling at a higher-ranked school instead of flourishing at someplace less selective?

Following last year’s Harvard decision, many journalists, activists and public intellectuals on the left were beside themselves, but the reaction among rank-and-file blacks was more muted. According to an Economist/YouGov survey, 47% of blacks supported the decision while 36% of blacks opposed it. Polling also showed that 35% of black respondents believed that racial preferences put them at a disadvantage, which was a higher amount than any other minority group.

That response didn’t surprise Gerald Early, a professor of African-American studies at Washington University in St. Louis. “Black Americans have had ambivalent feelings about affirmative action since its inception,” he wrote in the Chronicle of Higher Education after the ruling. “Though the extent and implications of the policy have changed radically over time, it has never benefited more than a small minority of Black people.”

Email:

Contact@dftdunite.org

Mailing Address:

PO Box 355

Davidson NC, 28036

Location:

Office Only - DO NOT MAIL

209 Delburg Street, Suite 107

Davidson, NC 28036

© 2022 All Rights Reserved | Davidsonians for Freedom of Thought and Discourse

Privacy Policy | Terms & Conditions | Disclaimer

Website powered by Neon One